Cope is Not a Strategy

Can Europe Only Hope for American AI to Stop Working?

There’s a particular school of European technology commentary that reads a lot like a bad ex-lover trying to conjure the malaise of the former partner (the United States). For example, the thesis that Marietje Schaake advances in the Financial Times and that animates Germany’s new €125 million Next Frontier AI initiative. The argument goes like this: American AI is a bubble. Bubbles burst. When this one does, Europe will be ready with its sensible, efficient, trustworthy alternative. Only, there is none in sight.

The main arguments go from sensible to cope really fast. Schaake, a former MEP and Stanford fellow, correctly states that businesses often don’t need the largest possible AI. A German car manufacturer doesn’t require a chatbot trained on the entire internet. It needs something trained on engineering data that can optimize manufacturing and predict maintenance failures. A Dutch hospital needs diagnostic tools that meet medical standards, not systems that occasionally hallucinate that you should drink turpentine for your cough. They need specialised AI capabilities. She argues that the hyperscalers are not what most businesses need and as soon as the bubble bursts the real value can be created by European models based on specialisation, trust, and safety. I’ll come back to this statement soon.

The SPRIND initiative makes a more sophisticated bet. They look at the current AI landscape which is dominated by what they call ‘insane data/compute/energy appetite’ and ‘scaling laws that favour whoever can burn the most H100s’. They conclude that Europe cannot win this game (which is probably correct). Instead, they propose hedging by funding research into alternative paradigms: sample-efficient learning, neuro-symbolic systems, energy-efficient architectures. This initiative is the single best thing that’s happening in the EU right now to advance frontier capabilities. SPRIND will do more for AI companies than all of the Commission combined and if it were up to me, I’d give them even more resources and leverage.

Under genuine uncertainty about whether current approaches will plateau, early positioning in alternative paradigms has option value. The question is whether €125 million buys meaningful optionality or merely funds a research program that, if successful, will be immediately absorbed by better-resourced American labs. At least it’s a hedge that only pays off under specific conditions: a paradigm shift must occur, it must occur soon enough that European labs can exploit it, and European labs must somehow defend their advantage against incumbents with 100x the capital. That’s a tiny window.

However, December 2025 has been an inconvenient reality check for this European idea of plateauing.

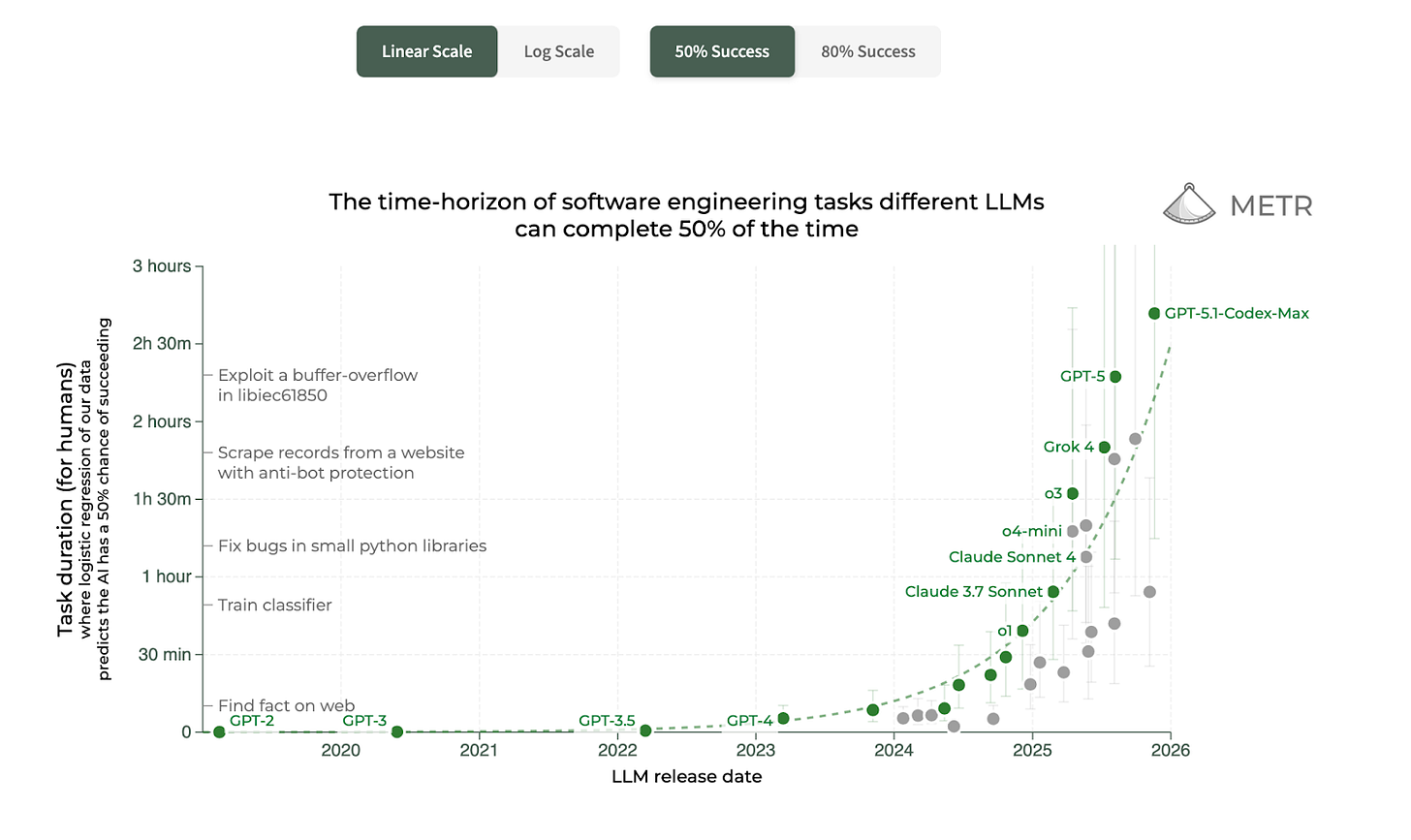

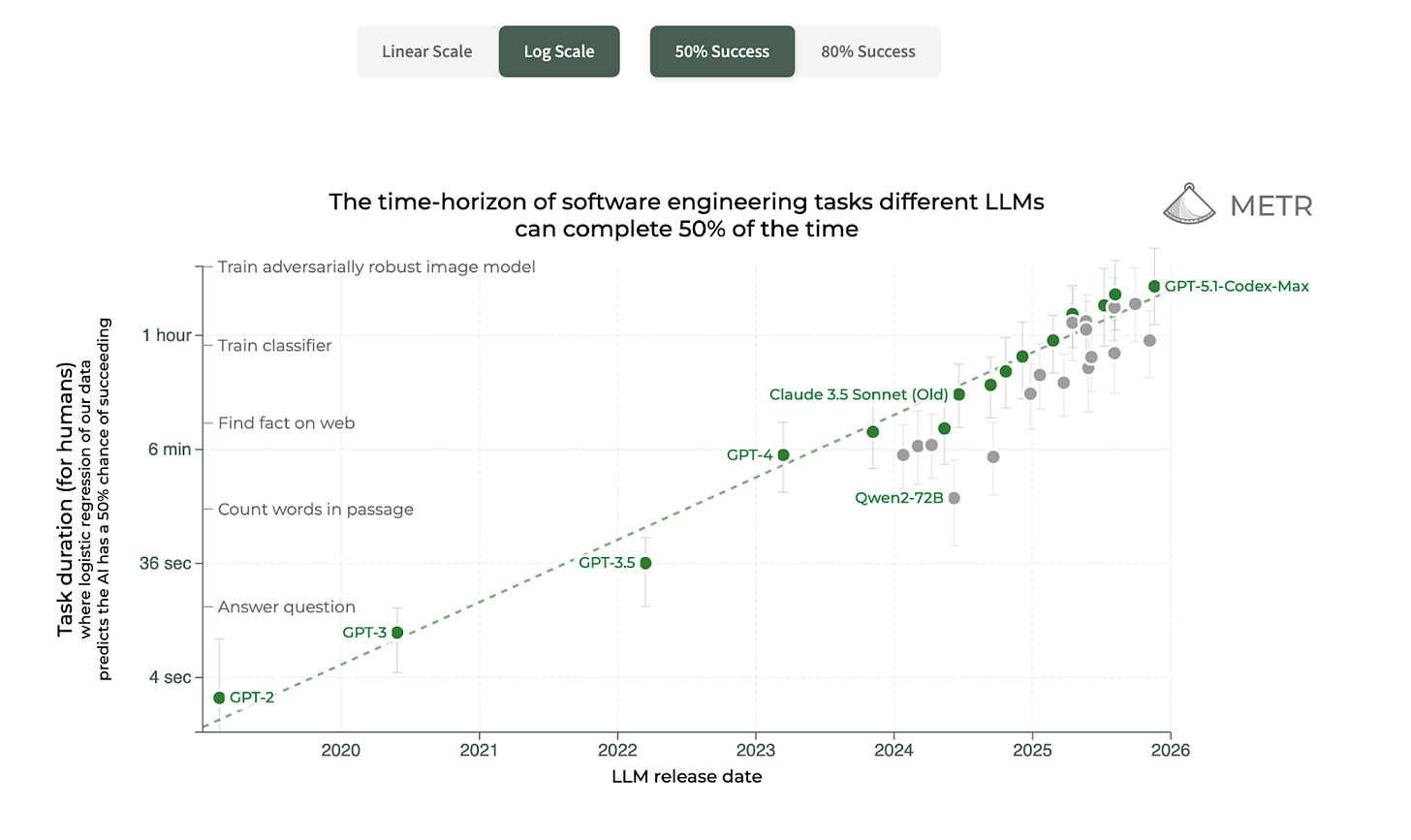

In August, OpenAI released GPT-5. In November, within the span of a single week, Google dropped Gemini 3 and Anthropic unveiled Claude Opus 4.5. Each release brought substantial, measurable improvements. The overall trend is still clearly exponential improvement with no sign of stopping at all.

GPT-5 scores 94.6% on advanced mathematics competitions without using tools. It hallucinates 45% less than its predecessor. Gemini 3 Pro hit 1501 Elo on the LMArena benchmark, the first model ever to break the 1500 barrier. On Humanity’s Last Exam, a test designed to be so hard that AI couldn’t pass it, Gemini scored 37.5%. The previous record was 31.6%. Claude Opus 4.5 now solves real-world software engineering problems better than any human candidate who has ever applied for a job at Anthropic.

Gemini 3 scored 31.1% on ARC-AGI-2, a benchmark specifically designed to test whether AI systems can generalize beyond their training data. Gemini 2.5, released just months earlier, scored 4.9%. That’s a sixfold increase on a test explicitly constructed to expose the limits of the current paradigm. Optimists see continued rapid progress; pessimists note that 31% still means failing two-thirds of problems designed to require generalization, and that rapid benchmark saturation often precedes plateaus. Whatever you make of that number, it shouldn’t be that progress in capabilities is slowing down in any way. The leapfrog thesis requires not just that current approaches eventually stall, but that they stall soon enough and hard enough to create an opening. Every month of continued progress narrows that window.

The Efficient Frontier

Here’s where the European idea runs into its most awkward problem: the efficiency gains they’re betting on are already being pioneered by the incumbents.

Claude Opus 4.5 introduced an ‘effort parameter’ that lets developers achieve the same performance as the previous model while using 76% fewer tokens. GPT-5.1 adapts its thinking time dynamically, it ponders hard problems and breezes through easy ones, rather than burning the same compute on everything. Anthropic cut its Opus pricing by 67% while delivering better results.

This is what monopolistic complacency looks like? The incumbents are simultaneously improving capability and efficiency and cutting prices? Some combustion engines.

The theory was that American labs, drunk on venture capital and racing to burn through compute, would neglect efficiency. Europe would build EVs while the US kept churning out Hummers. But it turns out, it’s the US again that builds the AI equivalent of the Tesla while Europe can’t build any serious player while still sneering down from its Castle in the Air floating on Good Intentions™©.

American labs also want to reduce costs and improve efficiency. That’s just how you make money and serve more users. The moment DeepSeek demonstrated in January that impressive results could be achieved with fewer resources, every major lab intensified their efficiency research.

There is no safe harbor of ‘efficient AI’ waiting for Europe to discover it. Efficiency is the game everyone is playing.

Before proceeding, it’s worth distinguishing questions that European strategy often conflates. First: Can Europe build frontier foundation models? Almost certainly not.

Second: Can Europe build valuable AI businesses? Possibly. Deployment, fine-tuning, and domain-specific applications don’t require frontier capabilities but they help immensely.

Third: Should Europe try to build frontier models, or accept dependency and optimize for other layers of the stack? This is a resource-allocation question, not a pride question.

Fourth: What does European ‘sovereignty’ actually require—full-stack independence, or merely optionality and leverage?

These questions have different answers, and a strategy that conflates them will optimize for the wrong goals. Most European AI rhetoric treats question one as decisive. It’s the least important of the four.

Where the Cope sets in

But what about the bubble? Surely these valuations are insane? OpenAI at $500 billion, Nvidia at $5 trillion, circular financing arrangements where companies invest in each other in dizzying loops of money that seems to exist primarily to justify more money?

Yes, probably! There’s almost certainly froth in AI valuations. Sam Altman himself said in August that investors are ‘overexcited about AI.’

But even if the Hyperscaler bubble would burst (and that’s a big If), there’s nothing for Europe to gain. The dot-com crash of 2000 did not create an opening for European internet companies to challenge American dominance. It killed a lot of weak startups, made capital more expensive, and left the strong players to grow into what they are today.

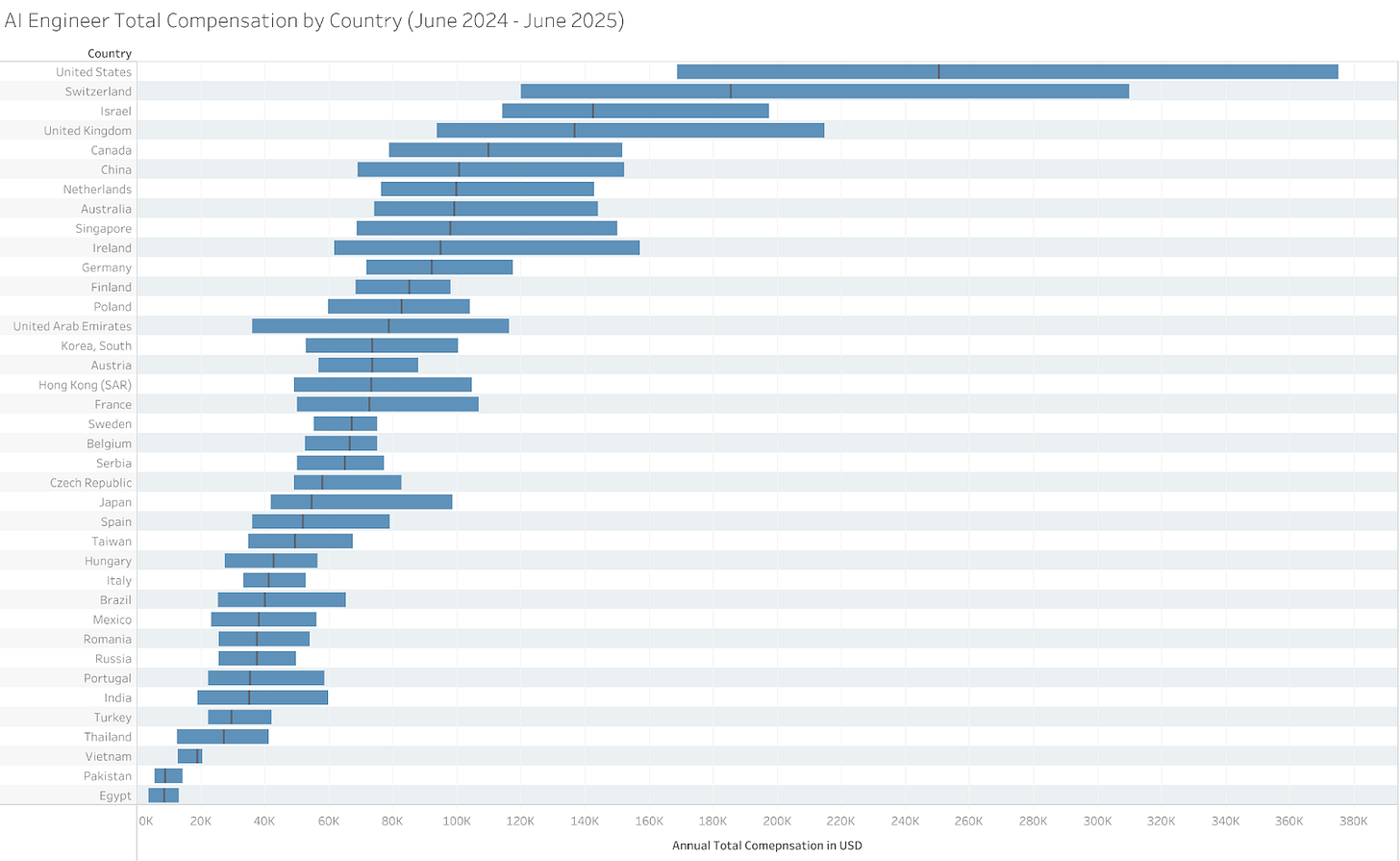

Schaake writes that ‘when the AI bubble bursts, valuations will reset, talent will become available.’ This is the part of her argument that I find most disconnected from reality. Look at this chart and tell me with a straight face that when the bubble bursts, American AI talent is going to flood into Europe.

The median AI engineer in the United States earns roughly $370,000. In Germany, it’s about $120,000. In France, $90,000. American AI engineers make three times what German ones make and four times what French ones make at much lower taxation rates.

When Schaake imagines ‘talent becoming available,’ what exactly does she think happens? A researcher making $400,000 at OpenAI gets laid off and thinks, ‘You know what, I’ve always wanted to take a 70% pay cut and move to Paris’? The Silicon-Valley-hackathon-type engineers who built GPT-5 will suddenly find Berlin’s clubbing scene irresistible?

When American AI companies downsize, that talent gets absorbed by other American AI companies. Or they start new companies in the Bay area.

The salary gap is precisely a feature of an ecosystem that has spent decades building the infrastructure to attract and retain technical talent. Europe could try to close this gap. But that would require paying competitive salaries, which would require generating competitive revenues, which would require... building competitive AI companies. Good luck with that if your best shot at that is apparently based on Chinese models:

https://x.com/rasbt/status/1999557830131494977

What Trust Actually Means

There’s a version of the European argument that I find more compelling, though it’s not quite the one being made.

Schaake talks about Europe building ‘the most trusted AI stack in the world.’ SPRIND mentions systems that are ‘controllable, auditable, and easier to align with European values from the start.’ But the European pitch can’t just be ‘our AI is worse, but you can trust it.’ If my life depends on it and you offer me a highly trustworthy european AI that is at best an undergraduate level intelligence, I still prefer my medical data to be assessed by the best american model, no matter who might have access to the data later.

Europe won’t beat the US at frontier AI. So the better argument Europeans could make is: “Frontier AI is not the strategic choke point. Deployment under legal constraint is.” AI will unfold arguably its highest impact in the most restrained areas: hospitals, government intelligence, national labs, national infrastructure. So the argument shouldn’t be any of the “we’ll catch up once you fail”-nonsense. Lawful, governable, and interpretable AI models should be trusted with all the spicy data. And once a frontier model fulfills the high European standards, they will be trusted and can be off improving the bureaucratic apparatus we call the EU through sheer Good Force. But again, Europe imagines itself to be in a morally superior position it’s just not in.

The fatal mistake in the European argument is the belief that American incumbents are structurally misaligned with trust.

They are not.

European rhetoric treats trust, auditability, and certification as matters of values and culture. But for incumbents, these are engineering and sales problems. And engineering and sales problems are precisely what large, well-capitalized technology firms excel at solving.

The moment regulated deployment becomes the bottleneck, American labs can and will adapt. Pharmaceutical companies internalized regulatory science when approval became the gate. Aircraft manufacturers did not lose to “more trustworthy companies”; they built safer planes.

There is nothing about OpenAI, Google, or Anthropic that prevents them from offering on-prem or air-gapped deployments, producing full audit logs, supporting certification workflows, or accepting liability under defined contractual regimes. In fact, their scale makes this easier, not harder. Compliance costs amortize across global markets. A European startup has to build trust instead of capability. A hyperscaler adds trust on top of capability.

Now assume, generously, that Europe is right anyway. Assume American labs move slowly. Assume Europe succeeds in carving out a niche as the world’s most trusted AI provider. What does that market look like?

It is regulated, slow, procurement-driven, risk-averse, and margin-constrained. Hospitals. Ministries. Statistical offices. Defense subcontractors. This is not a market that produces frontier-scale revenues, attracts top global talent, or generates fast iteration cycles and spillovers into general-purpose capability. It cannot bootstrap a sovereign AI ecosystem. At best, it sustains a compliance industry layered on top of someone else’s models.

And that is the conclusion the European argument never quite states out loud: even in its best-case scenario, Europe becomes a systems integrator, not a platform owner. And I’m so sick of the cope. Europe “leads” the world in privacy regulation, competition law, safety certification, and standards bodies. It does nothing to dominate operating systems, cloud platforms, semiconductors, social networks, or AI foundation models.

Which is why the “deployment under legal constraint” argument, for all its sophistication, still counts as cope. It reframes loss as wisdom and repeats the same structural error as the bubble narrative and the efficiency narrative before it. It assumes the leaders will fail to adapt, that constraints are secretly advantages, and that time will equalize structural asymmetries.

Trust and safety matter but they are the luxury coming after capability. A strategy that begins with “we cannot win at the core layer” and ends with “so the core layer doesn’t matter” is pure cope and cope is still not a strategy.

None of this means Europe should give up on AI. AI will reshape everything. But the path forward probably isn’t deluding yourself to believe in any slowdown that doesn’t seem to be happening.

I’m all for leveraging real strengths: manufacturing expertise, healthcare systems, financial services, automotive engineering, industrial data. These are domains where specialized AI applications can and will create enormous value. But for that to happen in Europe, we need to address the right issues: talent, capabilities, regulatory burden.

European universities still produce excellent AI researchers, even if many of them end up working in San Francisco. There might be ways to create environments where they’d want to stay. (Spoiler: it involves money. Look at the chart again.)

The most valuable thing Brussels can do is implement the AI Act narrowly, refrain from additional regulatory burden, and let member states compete. Germany can fix its broken stock option regime in one legislative session. France can create a 72-hour visa track for AI researchers with qualifying credentials. The Netherlands can extend and deepen its 30% tax ruling for researchers. European AI “sovereignty” is not a European project. It is a German, French, and Dutch project that the EU can support or hinder. Right now, the EU’s default is to harmonize, coordinate, and regulate. The right mode would be to enable, differentiate, and compete.

The competition between OpenAI, Google, and Anthropic is exactly what drives the American success. These are organizations staffed by obsessive people working crushing hours on a problem they believe is the most important in human history. They are not slowing down. I don’t see any sign that they will slow down anytime soon. And, as the salary data makes painfully clear, they’re paying whatever it takes to ensure the best people in the world work for them and not for anybody else.

In Germany we have the saying “It’s not an epistemological problem, we have an implementation problem” and the current public discourse repeats it like a parrot. I don’t think it’s true. I think we’re still lying to ourselves. Only through being honest to ourselves can we fix our problems. We have to rely more and more on ourselves, but that only works if we admit our faults and really do whatever it takes to get back up.

Because cope is not a strategy.